The Edition Wars

Published By: Derek on June 30th, 2014

When the fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons releases on July 3rd, I will have been playing the game for thirty-two years. I suppose this should make me feel old, but it doesn’t. I’ve played my way through every edition of the game, in all of its many forms and styles, and I’m really looking forward to this next incarnation.

Clearly, not all editions were created equal. To be sure, each had their highs and lows; their strengths and weaknesses. Yet, no edition can match the level of division in the gaming community that 4th edition managed to create. I experienced this division more intensely than most people, perhaps, because of my profession as a game store owner. It’s my job to share my opinion on products, and to listen to the opinions of others on the subject. How many comments, debates, and arguments have I been in over the last dozen years about which edition was best and why? What makes for a good game and what is sure to ruin one? Was THAC0 a good thing? I feel as though the long journey through (what will soon be five editions, plus one variant edition, and at least two important sub-editions) has brought me to a place that I am fairly confident in my ability to answer those questions – at least as the game pertains to me.

The early years

In 1982, my first experience with Dungeons & Dragons was with a friend who practically had to twist my arm to try it. I think back now how funny that was, considering the life-long path that my first experience with the game would propel me down. My reluctance to play nearly prevented me from trying it, and I still owe thanks to my friend Jacob Graham for his perseverance and insistence that things would be fun as soon as we finished rolling up that character. He was right.

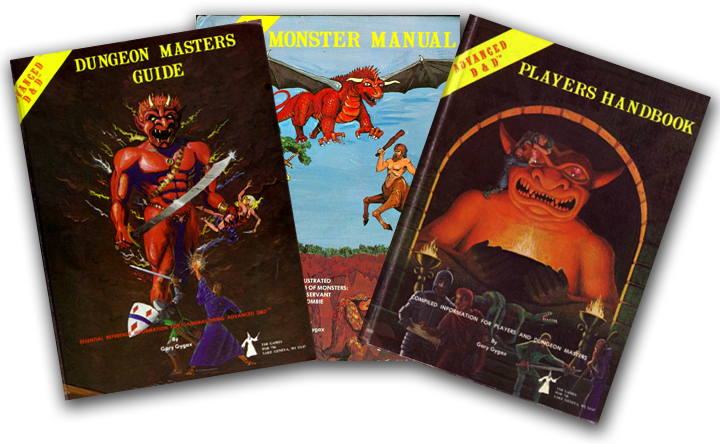

The edition I was first introduced to that weekend in the summer of 1982 was, not surprisingly, 1st edition. It had the lofty moniker: Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (why that word “Advanced” carried with it an almost mythical resonance to me for so long, I still cannot fully explain). When the reissue of the Advanced Dungeons and Dragons core books were released some time last year, I wrote an article about my experiences discovering the game, so I’ll avoid recounting them here. However, those first few years were an interesting time. Like most kids who come into D&D for the first time, I played the game “wrong” for the first two years. Which is to say, we ignored certain rules that we weren’t aware of, didn’t understand, or didn’t like. Characters tended to get extremely powerful very quickly, role-playing wasn’t really a focus, and the world practically rained magic items.

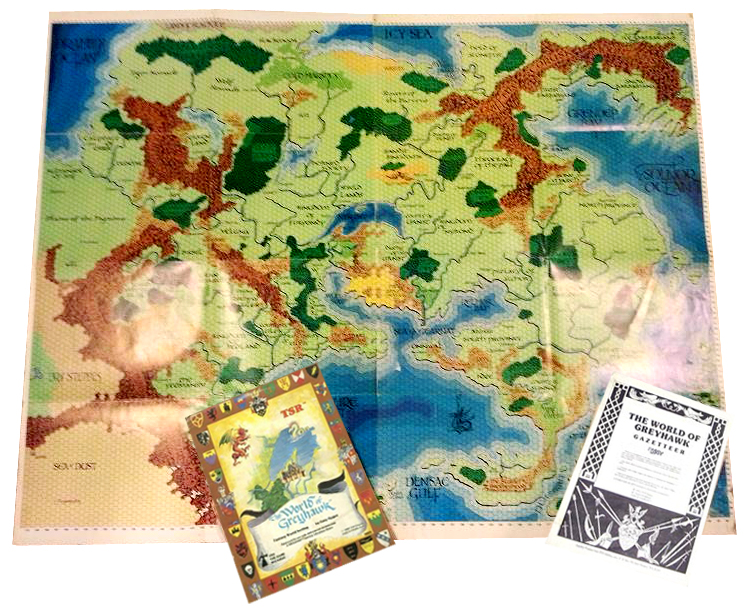

Sometime in late 1983, I began to get more serious about the rules and the game world we were playing in. TSR was the name of the company publishing D&D at that time, and the only campaign setting they had commercially made available was the World of Greyhawk, and I was drawn to it like a moth to a flame.

My friends and I had already played a few published adventure modules that had made reference to their location in the World of Greyhawk fantasy setting, so it was intriguing to find where those places were on the large, gorgeous, fold-out maps of Greyhawk’s busiest continent. Greyhawk became my chief love, and pretty much any adventure that I have run since 1983 has been set upon that exalted landscape. This is important to realize, and will help to explain why I view the 4th edition of Dungeons & Dragons to be such an enormous failure (more on that later).

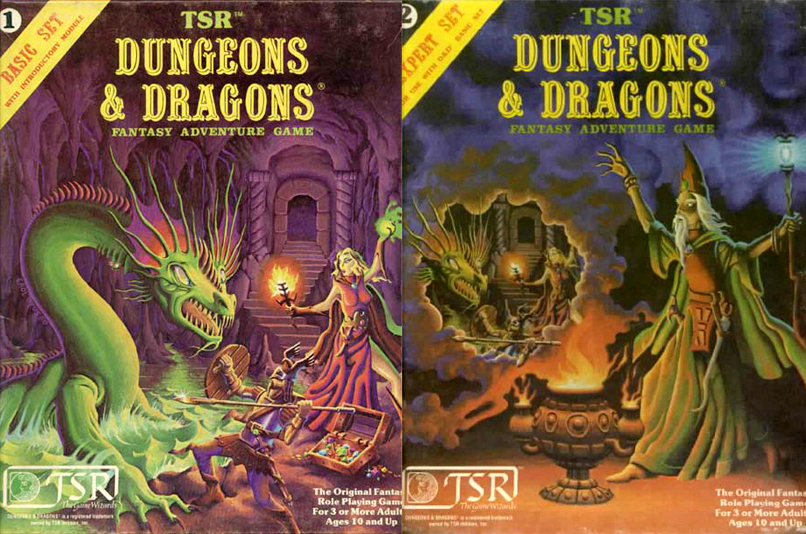

My experience with 1st edition ran the course of about four years (1982-1986). During that time, my friends and I also experimented with the Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set. Early in the article I referred to having played at least one “variant edition.” The Basic Set is what I meant by that. Basic D&D came self-contained in a red box, and covered the character levels of 1-3. I participated mostly as a player in those games, DMing once or twice. Added to Basic Set was a follow-up box called the Expert Set that provided additional rules that allowed for characters up to level 7.

To be honest, while I enjoyed those games, my real enthusiasm was always aimed at the more robust hardcover books of 1st edition. In these early days, I was still struggling to understand and implement the more complicated rules as I slowly waded my way through the oceans of 9-point font that filled the Dungeon Master’s Guide. By 1985 I had read the DMG from cover-to-cover and I believe it’s fair to say that I had “mastered the game.” From about that point forward, I was always the DM.

Second Edition

In 1986, TSR released Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition. There was quite a bit of excitement leading up to the release, but I must admit my initial experience and connection to the books was a bit of a dull thud. The artwork was pretty awful, the writing was rather drab, and a substantial amount of material seemed to have been “cut” from the game. For example, the half-orc and various elven sub-races disappeared as an optional player character race. The assassin and the monk vanished as optional classes. 1st edition had a rough, edginess to it, and 2nd edition seemed to have been run through the keep-it-squeaky-clean machine.

On the other hand, the game rules had certainly been made more immediately approachable. Archaic, nearly indecipherable mechanics like 1st edition’s rules for pummeling, grappling, and overbearing became considerably more sensible (but still awkward). Spells and their effects were homogenized and combat mechanics were significantly improved. Yet, overall, the two editions were largely compatible. A novice observing two games of differing editions played back-to-back probably wouldn’t even notice a difference. I was able to continue to incorporate elements that we liked from 1st edition with little to no effort at all. I was disappointed that the game had been polished so hard that some of its enamel had worn off, but I reminded myself that it was still early in the new edition. Expansion books would likely follow and the old edginess would return. It turns out, I was correct.

My Greyhawk campaign began to take on a much more serious tone during this era. I kept careful track of the passage of time. I utilized every rule as written and intended. We used miniatures to represent battles and dungeon exploration on the tabletop (a rarity in many games at that time). On occasion our gaming sessions would last for two or three days, punctuated only by short breaks to consume food and sleep. More players entered into my campaign setting and a sense of history began to develop. We would discuss old challenges the players had overcome, and deadly enemies yet to be faced. The World of Greyhawk took shape in all of our minds, becoming more rich and detailed and mysterious than any world from a novel or a movie could ever hope to achieve. Our game thrived.

This lasted for years, and my collection of gaming material grew and grew. Those who played during the era of 2nd edition D&D will remember the enormous amount of books that were released. The well known red, soft-cover “complete books” expanded the game for players in many ways. This is really where the notion of character customization concepts really took root. These books introduced a mechanic called “kits” (I still hate that name) that allowed players to receive a series of benefits that would, in theory, be balanced by a series of hindrances. This balancing theory usually resulted in failure, with the benefits or hindrances weighted too heavily one way or the other. Still, it was the means by which assassins, monks, and a host of sub-races returned to the game, and for that, we were happy.

This period represented the longest stretch we have ever had with one edition. For us, the era of 2nd edition lasted from 1986 through 1995. Not bad, I must say. There was a revision during that time, but it was mostly artistic in nature. The terrible blue-stamp artwork of the original books was replaced with a much more palatable selection of color art, and the format of the books was organized better and given a much-improved look.

In 1995, the Player’s Option books were released. These were not “officially” touted as a new edition of the game, but for all practical purposes they were. They were instead presented as an optional rules framework that allowed players and game masters to customize D&D in ways that allowed for a freer and yet much more complex play style. A whole book dedicated to a more complex method of running combat was introduced. Another book offering ways for players to create truly customized characters was published. Irritated that your super-genius wizard couldn’t spend a little time learning how to wield a longsword? The Player’s Option: Skills & Powers book had the answer for you. This book was followed shortly thereafter by another tome offering a host of new rules for magic in the game. Why can’t your wizard ever score a critical hit with a fireball? Player’s Option: Spells & Magic gave you the tools to make that happen. Lastly, there was a book offered up that gave rules for DMs to run extremely challenging high level game options. It was a great series (but not without its problems) and we really embraced them.

Then, for a variety of reasons, came the first dark period of D&D for me. First and foremost, the material being released for Dungeons & Dragons became increasingly scarce. Worse, the offerings were of poor quality and ultimately of little use. It was clear that something bad was happening to TSR. The Internet was still young in those days, and information leaked a little slower than it does now, but we eventually learned that the company that had produced Dungeons & Dragons for over twenty years was a sinking ship. Rumors of terrible mismanagement trickled down the pipe and the future seemed grim for our favorite game.

Additionally, most of the members of my long-standing gaming group had far less free time than we did in our younger days. College, jobs, relationships; all competed for people’s time, and adventures in the World of Greyhawk grew quiet. There were no local game stores for me to seek new players. No localized message boards for me to post “gamers wanted” ads. For a time, D&D seemed like it might need to be retired. Perhaps we’d dust off the old books someday when people were less busy and continue our saga.

Then word began to circulate that TSR had been sold to a company called Wizards of the Coast, the makers of the increasingly popular card game called Magic: The Gathering. In short time we also learned that a 3rd edition of D&D was in the making! As the Internet had become much more of an entity in everyone’s life we were able to follow the unfolding journey of D&D more closely. In 2000, some friends and I took the trip to Gen Con in order to be among the first people to get their hands on the new edition of the game.

We were not disappointed.

A new era

3rd Edition was exactly what we wanted. A wonderfully written set of rules, an enormous amount of options, a rekindling of Greyhawk right in the core rulebooks, and the promise of a bright future for our favorite game in the hands of a successful company. What’s more, the edition was very backwards compatible. With no real trouble at all, we managed to convert all of our old characters from previous editions to the 3rd edition rules. To our surprise (and as a testament to the 3rd edition’s versatility) the characters played very much like they had in 2nd edition. My long running Greyhawk campaign flourished once more and the detailed timeline of heroic events continued.

After two short years of gaming, Wizards of the Coast announced a revision to 3rd edition. It was met with audible groans from the collective online gaming community. It was perceived as a money-grab by Wizards, and everyone seemed indignant about shelling out more money to buy the core books all over again after only two years of usage. Personally, I welcomed the change. It was evident from our experience with playing 3rd edition that certain elements were “broken.” Anyone who was an active player during this period will know what I’m talking about. Power creep, as it has come to be known, was a real problem for most experienced gaming groups. Feat combinations and exponential stacking of spell effects made life hell for Dungeon Masters who wanted to provide a challenging game for his or her players. The revision was heralded as D&D 3.5 and after it was finally embraced by the masses everyone was forced to concede that the improvements to the game were worth the cost of buying the books again.

This era was important to me for a number of reasons. Not only was my Greyhawk campaign flourishing once more, my potential player base expanded into the unlimited range. I opened Battleground Games & Hobbies in November of 2002 and my involvement in my lifelong hobby became my business as well. The reign of 3rd edition D&D was a positive chapter in my D&D experience. Lots of great games were played and a host of new people became familiar with my old campaign, which by this time was over twenty years old.

Yet something happened again to thwart my enjoyment of Dungeons & Dragons. It began sometime after 2005, and it wasn’t obvious at first. By that time, many books had been added to the repertoire of tools for players to use in building their characters. Once again, D&D offered up a new series of “complete” books (this time in hardcover), presenting a variety of new options for them to choose as part of their character building process. These options did not always balance well, and it was extremely dubious as to whether or not any of them had been play-tested at all prior to the print release of the book.

Once more, it became difficult for DMs to provide balanced challenges for the player group. Characters became incredibly powerful and veteran players were amazing at having an answer for any and all foes they might face. Furthermore, the connection between players and the rules strengthened more than it had in previous editions. With their deep and expanding knowledge of the customization options available for players to utilize, control of the game could very easily slip out of the hands of the Dungeon Master, who was in all previous editions responsible for such things. This isn’t to say that good games couldn’t still be had. Every gaming group wants different things out of their game. But I stand by the notion that true mastery of D&D had transferred hands from DM to the player at a certain point after 2005. Something in the mystery of the game had been lost. That element of wonder and surprise was greatly depleted, and in my opinion, it came at the cost of immersion in the game world.

Nowhere was this more evident than in the release of two books which I feel rang the death knell for 3.5 D&D: The Spell Compendium and the Magic Item Compendium. The former introduced certain spells into the game that simply made the DMs job of providing balanced and challenging encounters infinitely more difficult. Certain spells in particular sounded suspiciously like they were written by a player best described by the now famous adjective: “munchkin.” Elemental Body anyone? Benign Transposition? Bombardment? Perhaps these problem spells were exclusive to my campaign. I’m sure worse examples can be culled from the tome, but my point should be clear. It used to be that the players had to react to challenges put forth by the DM. This makes the game exciting and realistic. By late 3.5 DMs were forced to constantly be reacting to challenges posed by the player’s and their characters. This had a distinctly negative impact on the immersion in the game.

For the latter example of the two books I cited above, consider this passage from the Magic Item Compendium:

“A player points to an item published in this book or the Dungeon Master’s Guide and asks, ‘Can I buy this?’ The answer should usually be, ‘Yes.’”

I remember blinking erratically for a few minutes after reading that passage as I realized with sudden impact that the game had slipped from my grasp. Beyond recovery? No, but I would certainly need to begin the struggle of reclaiming the game and restoring its lost verisimilitude. Modern players might not understand the reasons why a full and comprehensive knowledge of D&D’s enormous offering of magic items is a bad thing for most games. It’s harder to see when you come to the hobby through games like World of Warcraft or Diablo III or any other such game that treats magic items as less of a special thing and more a part of the intrinsic and essential part of the adventurer’s economy.

I realize the inherent absurdity in making the claim that an economy built on the buying and selling of magic items interferes with the realism of the D&D campaign. Is imagining an economy for magic items really that silly in a world where dragons rain fiery death from the skies, wizards shoot lightning from their fingertips, and adventurers live through a 50’ fall into a pit filled with poisoned spikes? Yes. Yes, it is. Perhaps in some future article, I’ll explain my reasons for holding that opinion. For now, I’d like to bring this tale to the end of 3rd edition, and into the D&D blackout of 4th edtion.

Fall from grace

What can be said of 4th edition that hasn’t already been blogged about ad nauseam? When the news of 4th edition hit the gaming stratosphere, people were not ready for it. This was the least of the editions problems, unfortunately. After all, people weren’t ready for 3.5 either, but it worked out just fine in the end. It was recognized then that solid changes were made to the game that resulted in a superior product and play experience. From early on, there were inklings that 4th edition was heading down the wrong road. Many months before the release of the edition, Wizards published a sneak-peek series of books that gave us our first view of some of the philosophy and design concepts that were being implemented in the new edition. I distinctly recall this passage rankling some feathers in Battleground when it was pointed out by one of our regulars:

“…when’s the last time you saw a PC make a Profession check that had a useful effect on the game? (Hint: If it was recently, your game is probably not as much fun as D&D should be. Sorry.)”

Here, we had a designer of the new edition telling players and DMs that enjoyed the idea of Profession checks in their campaigns that they weren’t having as much fun as they should be at the gaming table. Clearly, a game that once allowed for an enormously broad style of play was being directed to one particular style. To me, this is the equivalent of someone telling me that watching the Godfather films and enjoying the deep character development and sense of realism and tempered pacing is “less fun” than the latest, fast-paced trope from Michael Bay with its neat explosions and furious, hyperactive action.

As the release drew nearer, there was more troubling hints. Magic items now would be appearing in the Player’s Handbook for players to purchase and sell at will. In fact, doing so was an essential part of character leveling. Iconic character races and classes were being removed from the game and replaced with other, weirder and more fantastical races (dragonborn & tieflings). There was “DM advice” advocating the collection of magic item “wish lists” from all your players so that you could insert these items into the adventure for them to get the “kewl loot” they want. I futilely hoped that these ill tidings would not amount to an insurmountable problem.

The edition was a failure. Even in ways I had not anticipated.

Sales for the edition began strong as people desired to give it a fair shot. Games were played on the regular and Wizards instituted the Wednesday night D&D Encounters program to help get new players into the store and playing D&D. From a business standpoint, the merits to this type of game are obviously high. A system for people to show up to a store and be able to jump right into a game and start playing D&D is very good for exposing more new players to your product. But what about the old players? The ones who had been with the game since 1982 and beyond? Due to the extreme differences to how characters were constructed and functioned in the game, it was virtually impossible to convert characters from previous editions of the game to the new edition and have them play anything like they did before. “Yes, we are aware of this,” came the response from the D&D design team. “That’s why you should retire those characters and your old campaigns and start a brand new one using the 4th edition rules.”

For someone with a twenty-five year investment in their D&D campaign, these suggestions were the equivalent to telling me not to bother playing the game at all. Even still, I gave the game a fair shot. I “paused” the exploits of the players actively participating in my other games and started a new group adventuring in lands far away from the continent of my typical campaign setting.

It crashed and burned fairly quickly. It was crystal clear that this version of D&D was not for me (or for my players). It was a sinking ship right from the start, though we certainly gave it a solid try. I’ve touched on a few of the problems I had with the edition here and elsewhere. Online, the residual effects of the great 3rd vs 4th edition war still carries on. For me, the edition was dead within the first year of its release in 2008. There was a brief attempt to save the flailing edition in 2010 with the D&D Essentials revision, but it resulted in little more than a feeble whimper.

So where did I turn for my gaming fix? If you’ve come this far you must know that I would eventually mention Pathfinder.

Pathfinder is 3.5 Dungeons & Dragons with a different name and some minor tweaks to the core rules. It’s often jokingly (and accurately) referred to as D&D 3.75. I like to refer to it as a “legally stolen game.” Upon the release of the D&D 3rd edition rules, there was a revolutionary and daring document provided by Wizards of the Coast that allowed any publisher to produce material for the D&D game system, up to and including the reprinting of a significant portion of the actual rules themselves. This document, called the Open Game License, was a huge boon for 3rd edition at the time. It effectively created a guaranteed dominance in the role-playing game industry that kept Wizards of the Coast firmly established at the top. Ironically, this same innovation would ultimately work against them in equal portions when 4th edition D&D began to fail.

A company called Paizo, originally the authorized publishers of Dragon Magazine and Dungeon Magazine, using the Open Game License as their defense, reprinted and rebranded the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game as if it were their own. At first, its popularity was a small, sizzling flame, but as D&D 4th edition began to collapse, it rose to dominate the number one sales spot in the RPG industry. For the first time ever, the Dungeons & Dragons brand name had been usurped by another brand. Paizo puffed their chest about this quite frequently, which always rubbed me the wrong way. After all, this truthfully was not their game. When you are playing Pathfinder, you are playing a version of Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition.

Still, Pathfinder was the best of the available options for my game for the past four years or so. Some of the tweaks to the core rules were minor improvements over the 3.5 rules. Yet the large problems with 3rd edition’s ridiculous magic-item driven economy, player character power-creep, and issues with a DM’s ability to properly present challenges at higher levels all remained. These problems could not be fixed without a more proper treatment to the rules system.

My feeling is that we are about to get that treatment.

Dungeons & Dragons – 5th Edition

After the announcement of D&D 5th edition, I decided to put all my games on hold. It’s been over a year since I’ve run a game in my World of Greyhawk campaign. I’m pretty sure it’s the longest I’ve gone without running a D&D game since it all began back in 1982. I took the break for several reasons, but mostly it was because I realized that there just didn’t seem to be an edition for me anymore. 1st edition was great in its day, but too much had changed for me to step that far back into those archaic rules. 2nd edition had appeal briefly, but again, too many really solid improvements had been made in areas that really mattered for me to return to the magic of that era. 3rd edition’s problems were just too close to home for me to pick up and try again. These problems, having not been addressed to my satisfaction in 3.5 and Pathfinder ruled those choices out too. 4th edition wasn’t even considered.

To be fair, each edition, even the much maligned 4th edition, taught me something about what makes for a great D&D game. Immersion is the key. Good, solid rules, but not too many of them! Keep the math to a minimum while you’re actually at the table. Too many modifiers, too many combos and considerations, and you only succeed in pulling everyone out of the moment. We need a game that allows for adjustable speeds, so it can be tailored to each individual group. Restoring that lost sense of mystery to the game is essential too (keep those magic items in the DMG!). We need an edition that plays well at higher levels, so that when the time comes to pursue your worst enemies into the Abyss itself, you’ll have a good time doing it.

Based on the spoilers that I’ve seen so far, and the inside track I’ve been following on the Internet, it seems very likely that we might finally get the best edition of D&D yet. To me, it seems like a giant, positive step backward. Yet in the taking of that step the designers have raked back with them all of the best concepts and innovations that were presented in the later editions (and added a few new ones). In just a few more days we’ll have our first real peek at what the new edition will look like with the release of the Dungeons & Dragons Starter Set. It will be available at both Battleground locations on July 3rd, just in time to blow off all your 4th of July plans and spend it consuming the contents of the boxed set.

My Greyhawk campaign is about to begin again. Rising up and out of the ashes of the brutal Edition Wars.

May those wars finally be at an end.

Click on the image to preorder the Dungeons and Dragons 5th edition books and set!

Afterword

I am aware that I failed to mention the Original D&D folio booklets that were first published in 1974. This is for two reasons. The first is that I have only ever played them in a one-shot, retro style game. The second reason is that while they certainly hold a classic charm, they are more or less inferior to the much larger works that came later.

About the Author

Derek Lloyd is the owner of Battleground Games & Hobbies. He is a lover of games and a hater of all things Michael Bay. When he’s not behind the counter working hard to satisfy the needs of his customers, he can usually be found socializing and painting miniatures or terrain at the rear of the store. Besides games, he is also a fan of film, well thought-out discussions, and long walks on the beach. If anything was left out of this bio, then you can blame Sims because he’s the one who wrote it.

Join the Battleground Games & Hobbies community forums!

Please don’t forget to check us out on Facebook and follow us on Twitter @battleground_gh!

Social: